The Turbhe workshop of Primetals Technologies, situated ten miles east of the city of Mumbai, is home to 175 employees, making it the second-largest company location in India. The staff not only has comprehensive manufacturing expertise but also specializes in engineering work in the areas of electrics & automation and long rolling. A unique family atmosphere contributes to the location’s high productivity, feeling of camaraderie, and mutual support—support that Dr. Tom Widter greatly appreciated when he visited the location at the peak of the monsoon season …

An hour before my plane descends to Mumbai airport, the sky suddenly goes dark. Pitch black. Only minutes later, turbulence sets in, and the aircraft is shaken like a fish in a waterfall. Heavy rain lashes against the windows, effectively reducing outside visibility to zero. The monsoon is in full force, with everything it is known and respected for. Just how the pilots manage to bring down the aircraft, I don’t know, but when they do, everyone applauds.

As I exit the plane, I am greeted by humidity levels unknown to Europe. The moisture seems to have crept into everything, from the nice carpet floor at Mumbai airport and the papers at immigration to the sheets of the hotel bed that I fall into after a long day of travel. I go to sleep knowing that, the next morning, I will be taking a two-hour taxi ride to Primetals Technologies’ Turbhe location, 10 miles east of Mumbai, and that I'll be encountering some of India’s most extreme sides—including the slums, people washing their clothes in the river, barely drivable roads, and more of the relentless rain.

But from the moment I set foot in India, I also encountered incredible beauty, great kindness, and the country's very own tastes and smells. Never before have I seen women wear dresses as colorful and elegantly simple, strangers helping each other in the street, and youngsters celebrating the moment rather than focusing on their future and its uncertainties. It seems to me that Indians live for these wonderful mutual experiences.

A Place of Great Solidarity

Soon after my arrival at the company location, I talked to Sharad Budhia, who is Head of Metallurgical Services at Primetals Technologies India. He confirms my first impression of the Indian people: “The willingness to support one another is deeply ingrained in the Indian spirit,” he says. “It is amazing to watch the people of Mumbai during the monsoon season. Sometimes, it will rain so hard that traffic comes to a standstill. You can get stuck for hours and hours. And when that happens, the locals start to offer tea to complete strangers. They even serve them food, all out of compassion and solidarity. You will encounter this kind of hospitality in all of India, but particularly so in Mumbai. It is a very special place.” Budhia is noticeably happy to live in Mumbai, and he is pleased with the Turbhe company location, its capabilities, and especially its workforce.

His feelings are shared by Shyam Mishra, Head of Manufacturing in Turbhe. Mishra ensures that the site’s engineering and manufacturing capabilities are well aligned with the needs of the metallurgical services business, not just within India but worldwide. “I am particularly proud of our bending blocks, balancing blocks, Hydraulic Automated Gauge Control (HAGC) cylinders, shears, Morgoil bushings, and our various kinds of guides,” he says as he ushers me through the workshop. “Making these products requires great skill and accuracy, as well as dedication to quality. These items nicely showcase the competencies of our workshop.”

Products for a Worldwide Market

Walking through the workshop, Mishra and I stop at a large pile of what he tells me are water-box nozzles. “We make around 5,000 to 6,000 of those per year,” he says. “A large quantity is exported to the USA and other countries.” No wonder the nozzles are in high demand: as I inspect them more closely, the sheer quality of manufacturing is strikingly evident. They have been made with great precision, and they are so consistent that I could not tell one from another.

As we continue to explore the site, Mishra turns to workman Mahendra Jambhle, who has just finalized several insert cooling nozzles, which will be used in the water-box assembly by a Polish customer. Satisfied with his work, he shows us the manufacturing steps he has followed to ensure high product quality and reliability. Watching him, I can tell that he is passionate about what he does and also highly skilled and experienced. He knows exactly what his machine is doing at any point in time.

I soon realize just how many different kinds of products the Turbhe workshop is capable of making. We pass by a worker manufacturing insert RE-150 elements, which are rugged and weighty and look utterly indestructible. The workshop offers much to the eye, and it is hard to choose what to focus on next. We arrive at our last stop in the small-machining section of the workshop, where Sanket Kolaskar is manufacturing nozzle components using a piece of equipment that was installed only recently. “This machine was actually inaugurated by our CEO, Satoru Iijima, a few weeks ago,” Kolaskar informs me. As he says it, I notice a specially designed plaque attached to the machine with Iijima’s name and photo. “We are all one company,” workshop head Mishra points out. "It was great to show our CEO what we can do here, and I think that he was very pleased."

The Large-Machining Section

The workshop is split into two main segments: the small-machining section, where we started our walk, and the large-machining section, which we are now entering. We turn our attention to a product significantly larger than any of the previous ones, a bending block. “It takes about 150 man-hours to make one of these,” Mishra explains. “We start with just a large square piece of metal and then ‘sculpt’ it until the final bending block has emerged,” I remember the famous quote by Michelangelo, who was asked how he went about creating his marvelous sculptures. “When I make a lion, I simply chip away everything that does not look like a lion,” he is believed to have said. The workshop staff at Turbhe might follow a similar approach, if arguably with a somewhat more practical goal in mind.

Surprised by the size and high utilization of the workshop area, I ask Mishra how many employees he currently manages. “In the workshop area alone, we are now employing 66 people, if I count both the workshop staff and those of our office workers who directly support the workshop,” he says. “Additionally, we have up to 22 contractor-sourced workers on site, and a staff of 7 who are assigned to supply-chain related tasks.” Most workers are on rotation, learning to master the relevant work processes on several machines. This measure both strengthens the team spirit and ensures that overall operations can be easily maintained in case someone is involuntarily absent.

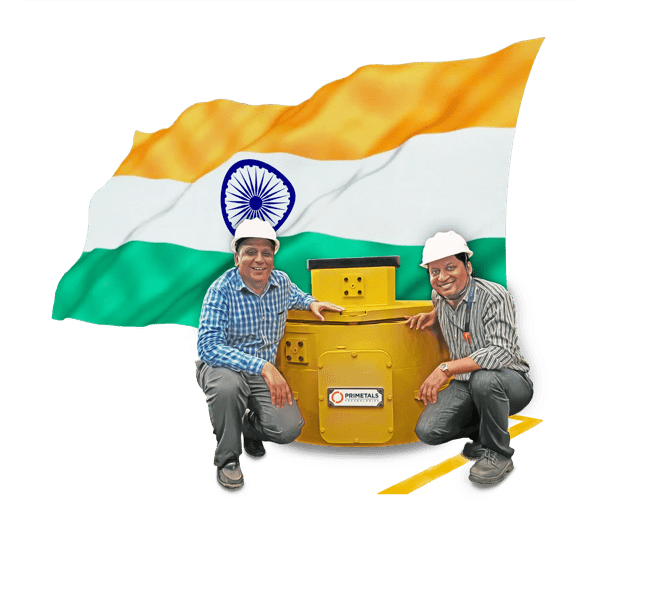

The large-machining section features some pretty impressive equipment. HAGC cylinders can be tested on site with a high-pressure HAGC testing stand. Shyam Mishra guides me to a yellow-colored HAGC cylinder that his team has just finished reconditioning. They are very happy with the end result—and they are confident that their customer will feel the same way. Mishra then takes me to a room in which he keeps the babbitt-welding equipment. With the monsoon season in full swing, babbitt welding is currently on hold. Some of the workshop’s gear is even covered in plastic to make sure that the moisture doesn't affect its operability. Since the workshop’s overall portfolio is large and the production pipeline is well-scheduled, this is not a problem.

Owing to this quite extensive portfolio, not all of the products made at the workshop were being manufactured at the time of my visit. An especially impressive product, the Heavy Duty 1080 Shear, was recently exported to Brazil but is not “on display” at the moment for me to photograph. The same is true for some of the larger chocks made in Turbhe. Those were recently shipped to Canada, the U.S.A., Mexico, Indonesia, and other countries. I luckily do encounter a newly made Morgoil bushing, a remarkable and highly sought-after product, huge in size and extremely evenly manufactured.

Expertise in Guide Manufacturing

Guides for handling stock in rolling lines are another one of the workshop’s specialties. Many customers require custom guide designs, which the workshop staff and the on-site engineers tackle in close collaboration. In many cases, some ingenuity will be required, and the staff will go to great lengths to ensure customer satisfaction. “A while ago, a steel producer desperately required new guides but was a bit doubtful that our solution would work for them,” I am told. “To convince them, we gave them the opportunity to examine the new guide concept directly in their facility. We implemented a quite elaborate test setup, which worked extremely well and gave the customer the assurance they needed to go ahead and purchase it.” I ask Mishra how much customization work the factory usually handles. “Depending on the situation, about 10 to 15 percent of our total work volume at a given time will be customization work,” he replies. “That figure will likely increase in the future.”

On our way back to the small-machinery area, we walk by a large stack of Entry and Receiving (ERG) guides. The workshop manufactures these guides in large quantities, and much of the production is exported to countries such as the USA, Argentina, Mexico, Taiwan, and the Czech Republic. Speaking to Mishra, it turns out that this type of guide is actually one of the simpler ones, and that the workshop makes a variety of much more complex guides for the local and overseas markets.

Why Safety Comes in Cans

As we conclude our workshop tour, Mishra and I stop at a large wall covered with posters drawn by the staff. We look at several dozen of the sketches, which the workers came up with to remind themselves to focus on their own safety and that of their colleagues. Some of the drawings strike a more serious note, some are more lighthearted, and some are openly amusing. I particularly like one that reads, “Safety comes in cans: I can, you can, we can.” The kind of humor found here might be a bit outlandish for some, but it does drive home the point that the initiative is trying to make.

“Your family needs you. Work safe for yourself,” reads another one of the workers' drawings. Studying it, I get the feeling that in a way the entire staff at the Turbhe location is very close to being a big family in its own right—a family not by birth but by choice. Mishra confirms my impression: “Absolutely, this is a very family-like workshop with very high safety standards, well maintained, and with a medical facility on site. We look after each other here, and we take good care of the workshop in general.”

Ready for the Digital Future

Mishra and I now head back to the conference room for a final discussion. I wonder what's best to ask him to find out more about the outlook for the location, and I settle for digitalization as a keyword. How will the trend toward Industry 4.0 impact the workshop? “All of our production machines are already fully automated,” Mishra says. “Aside from that, and speaking more strictly about digitalization, we are currently conceptualizing what changes we will be making to optimally support the steel industry in this development. These changes mostly concern us on a plant level rather than on a product level. They might take some time, but in the end, they will greatly improve our operations.”

Does he think that there will be job losses in the steel industry—and potentially in his workshop—due to intelligent machines taking over? His answer is one of the smartest and to-the-point statements I have come across on the subject matter. “I am pretty fearless in this regard,” he says. “Job loss has never happened because of advancements in technology, but because of a lack of training. Here, we have to be strong and think ahead. And we will.” He certainly has me convinced that the Turbhe staff will rise to the challenge.

Thank you, India

After three days at the Turbhe workshop, my visit comes to an end. I have learned a lot about the place, not just about the company location, but the Mumbai area as well. I have learned not to interpret the kindness of strangers as deception (a taxi driver tried to trick me, and I had a hard time trusting hotel staff with my luggage afterward); I have learned about the benefits of vegetarian cuisine; I have seen just how much even the poorest of us are capable of enjoying the moment—for instance, teenagers dancing in the rain, making music, celebrating life as it comes. Most importantly, I have learned to surrender my intellect when I notice that something is simply beyond my understanding. India's culture is without equal, and with one week’s worth of experience, I have barely scratched the surface.

Waiting at Mumbai airport for my 3 a.m. flight to start boarding, I wonder what role India might play in the coming decades. It's people made a huge impression on me: Not only were they extremely friendly and open, but they were also prepared to see the world around them with a clarity I have not encountered anywhere else. They were ready to take their future at face value. And no matter what role someone played, major or minor, they knew where they fit in—in the larger scheme of things. In the many interviews I did in Turbhe, I found that everyone had an acute sense of what was around the corner, technologically, economically, and politically.

I enter the plane, and just as it takes off and leaves the monsoon behind, I decide to conclude my story with a prediction: I'd be willing to bet that by the time our still nascent century ends, some of its greatest visionaries, innovators, and pioneers will have come from India. I have seen the country’s potential, I have felt it, and I must say that I profoundly believe in it. I only hope that those future greats will stay in their home country—and make India the essential player on the world stage it deserves to be.